Honors students pitch innovative solutions to Lake Erie’s biggest problems

For the past semester, students in the natural sciences honors colloquium course “Open Science for Clean Water” have been investigating technological solutions to Lake Erie’s most pressing problems, including the outbreak of harmful algal blooms (HABs), or cyanobacteria, that have been turning the lake green with a toxic goo each summer.

On May 4, teams of students from The Drs. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College pitched their solutions to industry experts and faculty members. Their proposals ranged from creating a middle school curriculum for a smartphone-based, spectrometer monitoring device that can detect algae-producing nutrients (phosphates and nitrates) in water samples to a massive anaerobic digester machine that would convert nutrient-rich manure (another contributor to HABs) into organic fertilizer and natural gas.

Other proposals included data-collecting sensors that attach to buoys and the use of duckweed and watermeal to remove, and carbon steel wool to filter, phosphates and nitrates from the lake and its watershed.

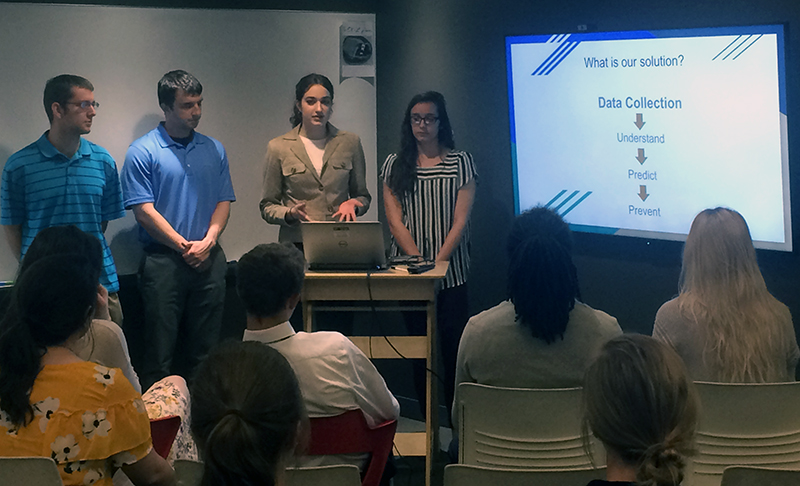

Explaining the need for collecting data about water quality to predict and prevent algal blooms is the team of Stephen Sykes, civil engineering major; Mark Wysocki, mechanical engineering major; Nicole Wiswesser, speech-language pathology and audiology major; and Abigail Sovacool, nursing major.

The course blended the format of an honors colloquium and an “unclass,” an interdisciplinary experiential learning course offered through our Center for Experiential Learning (EX[L] Center), in that it enabled students of diverse academic disciplines to collaborate in hands-on, problem-based learning.

“The goal is to present students with an issue – in this case, a threat to clean water – and maybe two or three other ways people have approached this issue, and then determine their strengths, find out what inspires them, and support them as they build the class from there,” says Dr. Carolyn Behrman, co-director of the EX[L] Center, housed in Bierce Library, where students delivered their final pitches. “They have some control over the way the class unfolds – and they respond to this responsibility with a great deal of energy and intelligence.”

The course was modeled after last year’s Erie Hack pitch competition, hosted by the Cleveland Water Alliance (CWA), in which coders, developers, engineers and water experts were challenged to come up with creative ways to combat HABs and other pollutants plaguing Lake Erie.

Dr. Hunter King, assistant professor of polymer science and core member of UA’s Biomimicry Research Innovation Center (BRIC), co-taught the course with Kelly Siman, doctoral candidate and BRIC biomimicry fellow sponsored by CWA. Both King and Siman, through their startup Open Erie Spec, helped build the spectrometer used by the students. They invited Max Herzog, CWA program manager, to present the Erie Hack-inspired challenge at the beginning of the course, connect students with experts in the field and provide feedback at the midterm and final pitch presentations.

“Not only the ideas, but the depth of their ideas – looking at how they could be implemented, scaled and funded, for example – was impressive,” says Herzog. He presented questions and advice to students after hearing their final pitches, and was part of a panel that included Pat Lorch, manager of field research at Cleveland Metroparks, and Dr. Dane Quinn, professor of mechanical engineering and associate dean of undergraduate research for the Williams Honors College, and Dr. Donald Visco, dean of the College of Engineering.

Gavin DeMali, a sophomore geology student on the “Phyto Phyters” team, which proposed the use of phytoremediation, specifically via duckweed and watermeal, to mitigate nutrient pollution, says the course was “the single greatest hands-on learning experience” he has had at UA.

“The students did everything,” Siman says, adding that they represented majors ranging from biology and nursing to finance and engineering. “When you don’t just lecture at students, but let them dive into something they’re interested in, they soar.”

“The point was to empower the students to use any available skill and creativity to exactly contribute to a real-world solution,” King adds. “It is not an exercise for when this might be ‘really’ done when they grow up, but their best shot at fixing the problem now.”

Siman, who hopes to offer a similar course in the spring, says four of the students will continue research on their projects, either for senior capstones or honors projects, three intend to submit their research to a peer-reviewed academic publication, and two earned Tiered Mentoring positions in the lab of their choice in the Department of Biology.